Lesson 1. The Syntax of the R Scientific Programming Language - Data Science for Scientists 101

Get to Know R - Earth analytics course module

Welcome to the first lesson in the Get to Know R module. This module introduces the R scientific programming language. You will work with precipitation and stream discharge data for Boulder County to better understand the R syntax, various data types and data import and plotting.In this tutorial, you will explore the basic syntax (structure) or the R programming language. You will learn about assignment operators (<-), comments (#) and functions as used in R.

Learning Objectives

At the end of this activity, you will be able to:

- Understand the basic concept of a function and be able to use a function in your code.

- Know how to use key operator commands in

R(<-).

What You Need

You need R and RStudio to complete this tutorial. Also we recommend that you have an earth-analytics directory set up on your computer with a /data directory within it.

In the previous module, you set up RStudio and R and got to know the RStudio interface. You also created a basic RMarkdown report using RStudio. In this module, you will explore the basic syntax of the R programming language. You will learn how to work with packages and functions, how to work with vector objects in R and finally how to import data into a data.frame which is the R equivalent of a spreadsheet.

Let’s start by looking at the code you used in the previous module. Here you:

- Downloaded some data from figshare using the

download.file()function. - Imported the data into

Rusing theread.csv()function. - Plotted the data using the

qplot()function (which is a part of theggplot2package).

# load the ggplot2 library for plotting

library(ggplot2)

# turn off factors

options(stringsAsFactors = FALSE)

# download data from figshare

# note that you are downloading the data into your

download.file(url = "https://ndownloader.figshare.com/files/7010681",

destfile = "data/boulder-precip.csv")

# import data

boulder_precip <- read.csv(file = "data/boulder-precip.csv")

# view first few rows of the data

head(boulder_precip)

## X DATE PRECIP

## 1 756 2013-08-21 0.1

## 2 757 2013-08-26 0.1

## 3 758 2013-08-27 0.1

## 4 759 2013-09-01 0.0

## 5 760 2013-09-09 0.1

## 6 761 2013-09-10 1.0

# what is the format of the variable in R

str(boulder_precip)

## 'data.frame': 18 obs. of 3 variables:

## $ X : int 756 757 758 759 760 761 762 763 764 765 ...

## $ DATE : chr "2013-08-21" "2013-08-26" "2013-08-27" "2013-09-01" ...

## $ PRECIP: num 0.1 0.1 0.1 0 0.1 1 2.3 9.8 1.9 1.4 ...

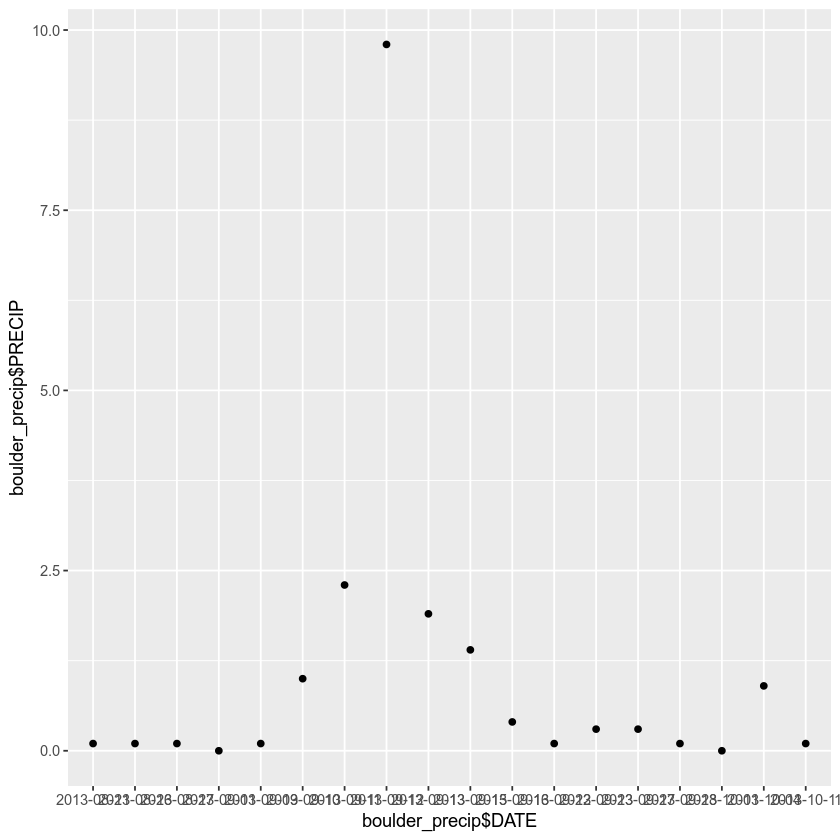

# q plot stands for quick plot. Let's use it to plot your data

qplot(x = boulder_precip$DATE,

y = boulder_precip$PRECIP)

The code above uses syntax that is unique the R programming language. Syntax is the characters or commands that R understands and associated organization / format of the code including spacing and comments.

Let’s break down the syntax of the code above, to better understand what it’s doing.

Intro to the R Syntax

Assignment Operator <-

First, notice the use of <-. <- is the assignment operator. It is similar to an equals (=) sign. It assigns values on the right to objects on the left. So, after executing x <- 3, the value of x is 3 (x=3). The arrow can be read as 3 goes into x.

In the example below, you assigned the data file that you read into R named boulder-precip.csv to the variable name boulder_precip. After you run the line of code below, what happens in R?

# import data

boulder_precip <- read.csv(file = "data/boulder-precip.csv")

# view new object

boulder_precip

## X DATE PRECIP

## 1 756 2013-08-21 0.1

## 2 757 2013-08-26 0.1

## 3 758 2013-08-27 0.1

## 4 759 2013-09-01 0.0

## 5 760 2013-09-09 0.1

## 6 761 2013-09-10 1.0

## 7 762 2013-09-11 2.3

## 8 763 2013-09-12 9.8

## 9 764 2013-09-13 1.9

## 10 765 2013-09-15 1.4

## 11 766 2013-09-16 0.4

## 12 767 2013-09-22 0.1

## 13 768 2013-09-23 0.3

## 14 769 2013-09-27 0.3

## 15 770 2013-09-28 0.1

## 16 771 2013-10-01 0.0

## 17 772 2013-10-04 0.9

## 18 773 2013-10-11 0.1

Data Tip: In RStudio, typing Alt + - (push Alt at the same time as the - key) will write ` <- ` in a single keystroke.

While the = can be used in R, it does not always work. Thus you will use <- for all assignments in R from here on in. It is a recommended best practice.

When you are defining arguments for functions you do use the = sign. You will learn about function arguments below.

Data Tip: Check out the links below for discussions on using = vs <- in R.

Comments in R (#)

Next, notice the use of the # sign in your code example.

# load the ggplot2 library for plotting

library(ggplot2)

Use # sign is used to add comments to your code. A comment is a line of information in your code that is not executed by R. Anything to the right of a # is ignored by R. Comments are a way for you to DOCUMENT the steps of your code - both for yourself and for others who may use your script.

Functions and Their Arguments

Finally you have functions. Functions are “canned scripts” that automate a task that may otherwise require typing in several lines of code.

For example:

# take the square root of a value

sqrt(16)

## [1] 4

In the example above, the sqrt function is built into R and takes the square root of any number that you provide to it.

Function Arguments

A function often has one or more inputs called arguments. In the example above, the value 16 was the argument that you gave to the sqrt() function. Below, you use the qplot() function which is a part of the ggplot2 package. qplot() needs two arguments to execute properly:

- The value that you want to plot on the

x=axis - The value that you want to plot on the

y=axis

# q plot stands for quick plot. Let's use it to plot your data

qplot(x = boulder_precip$DATE,

y = boulder_precip$PRECIP)

Functions return an output. Sometimes that output is a figure like the example above. Sometimes it is a value or a set of values or even something else.

Base Functions vs. Packages

There are a set of functions that come with R when you download it. These are called base R functions. Other functions are add-ons to base R. These functions can be loaded by

- Installing a particular package (using install.packages() like you did when you installed

ggplot2,knitr, andrmarkdownand loading the library in your script using `library(package-name). - Writing your own functions.

Functions that Return Values

The sqrt() function is an example of a base R function. The input (the argument) is a number, and the return value (the output) is the square root of that number. Executing a function (‘running it’) is called calling the function. An example of a function call is:

b <- sqrt(a)

Here, the value of a is given to the sqrt() function, the sqrt() function calculates the square root, and returns the value which is then assigned to variable b. This function is very simple, because it takes just one argument.

Let’s run a function that can take multiple arguments: round().

# round a number

round(3.14159)

## [1] 3

Here, you’ve called round() with just one argument, 3.14159, and it has returned the value 3. That’s because the default is to round to the nearest whole number. If you want more digits you can see how to do that by getting information about the round function. You can use args(round) or look at the help for this function using ?round.

# view arguments for the round function

args(round)

## function (x, digits = 0)

## NULL

# view help for the round function

?round

You see that if you want a different number of digits, you can type digits=2 or however many you want.

round(3.14159, digits = 2)

## [1] 3.14

If you provide the arguments in the exact same order as they are defined you don’t have to name them:

round(3.14159, 2)

## [1] 3.14

And if you do name the arguments, you can switch their order:

round(digits = 2, x = 3.14159)

## [1] 3.14

It’s good practice to put the non-optional arguments (like the number you’re rounding) first in your function call, and to specify the names of all optional arguments. If you don’t, someone reading your code might have to look up definition of a function with unfamiliar arguments to understand what you’re doing.

Get Information About a Function

If you need help with a specific function, let’s say barplot(), you can type:

?barplot

If you just need to remind yourself of the names of the arguments, you can use:

args(lm)

Optional Challenge Activity

Use the RMarkdown document that you created as homework for today’s class. If you don’t have a document already, create a new one, naming it: “lastname-firstname-wk2.Rmd. Add the code below in a code chunk. Edit the code that you just pasted into your .Rmd document as follows:

- The plot isn’t pretty. Let’s fix the x and y labels. Look up the arguments for the

qplot()function using either args(qplot) OR?qplotin the R console. Then fix the labels of your plot in your script.

HINT: Google is your friend. Feel free to use it to help edit the code.

- What other things can you modify to make the plot look prettier. Explore. Are there things that you’d like to do that you can’t?

# load the ggplot2 library for plotting

library(ggplot2)

# download data from figshare

# note that you are downloading the data into your

download.file(url = "https://ndownloader.figshare.com/files/7010681",

destfile = "data/boulder-precip.csv")

# import data

boulder_precip <- read.csv(file="data/boulder-precip.csv")

# view first few rows of the data

head(boulder_precip)

# when you download the data you create a dataframe

# view each column of the data frame using it's name (or header)

boulder_precip$DATE

# view the precip column

boulder_precip$PRECIP

# q plot stands for quick plot. Let's use it to plot your data

qplot(x = boulder_precip$DATE,

y = boulder_precip$PRECIP)

Share on

Twitter Facebook Google+ LinkedIn

Leave a Comment