Lesson 2. GIS in Python: Intro to Coordinate Reference Systems in Python

Learning Objectives

- Be able to describe what a Coordinate Reference System (

CRS) is. - Be able to list the steps associated with plotting 2 datasets stored using different coordinate reference systems.

Intro to Coordinate Reference Systems

The short video below highlights how map projections can make continents look proportionally larger or smaller than they actually are.

What is a Coordinate Reference System

To define the location of something you often use a coordinate system. This system consists of an X and a Y value located within a 2 (or more) -dimensional space.

While the above coordinate system is 2-dimensional, you live on a 3-dimensional earth that happens to be “round”. To define the location of objects on the earth, which is round, you need a coordinate system that adapts to the Earth’s shape. When you make maps on paper or on a flat computer screen, you move from a 3-Dimensional space (the globe) to a 2-Dimensional space (your computer screens or a piece of paper). The components of the CRS define how the “flattening” of data that exists in a 3-D globe space. The CRS also defines the the coordinate system itself.

A coordinate reference system (CRS) is a coordinate-based local, regional or global system used to locate geographical entities. – Wikipedia

The Components of a CRS

The coordinate reference system is made up of several key components:

- Coordinate System: the X, Y grid upon which your data is overlayed and how you define where a point is located in space.

- Horizontal and vertical units: The units used to define the grid along the x, y (and z) axis.

- Datum: A modeled version of the shape of the earth which defines the origin used to place the coordinate system in space. You will explain this further, below.

- Projection Information: the mathematical equation used to flatten objects that are on a round surface (e.g. the earth) so you can view them on a flat surface (e.g. your computer screens or a paper map).

Why CRS is Important

It is important to understand the coordinate system that your data uses - particularly if you are working with different data stored in different coordinate systems. If you have data from the same location that are stored in different coordinate reference systems, they will not line up in any GIS or other program unless you have a program like ArcGIS or QGIS that supports projection on the fly. Even if you work in a tool that supports projection on the fly, you will want all of your data in the same projection for performing analysis and processing tasks.

Data Tip: Spatialreference.org provides an excellent online library of CRS information.

Coordinate System & Units

You can define a spatial location, such as a plot location, using an x- and a y-value - similar to your cartesian coordinate system displayed in the figure, above.

For example, the map below shows all of the

continents in the world, in a Geographic Coordinate Reference System. The

units are Degrees and the coordinate system itself is latitude and

longitude with the origin being the location where the equator meets

the central meridian on the globe (0,0).

Next, you will learn more about CRS by exploring some data. Note that you don’t need to actually submit anything reviewed in this lesson for your homework. It’s just a way to show you how the CRS impacts your data.

import os

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.ticker import ScalarFormatter

import seaborn as sns

import geopandas as gpd

from shapely.geometry import Point

import earthpy as et

# Adjust plot font sizes

sns.set(font_scale=1.5)

sns.set_style("white")

# Set working dir & get data

data = et.data.get_data('spatial-vector-lidar')

os.chdir(os.path.join(et.io.HOME, 'earth-analytics'))

To begin, load a shapefile using geopandas.

# Import world boundary shapefile

worldBound_path = os.path.join("data", "spatial-vector-lidar", "global",

"ne_110m_land", "ne_110m_land.shp")

worldBound = gpd.read_file(worldBound_path)

Plot the Data

# Plot worldBound data using geopandas

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 5))

worldBound.plot(color='darkgrey',

ax=ax)

# Set the x and y axis labels

ax.set(xlabel="Longitude (Degrees)",

ylabel="Latitude (Degrees)",

title="Global Map - Geographic Coordinate System - WGS84 Datum\n Units: Degrees - Latitude / Longitude")

# Add the x y graticules

ax.set_axisbelow(True)

ax.yaxis.grid(color='gray',

linestyle='dashed')

ax.xaxis.grid(color='gray',

linestyle='dashed')

Create Spatial Points Object

Next, add three coordinate locations to your map. Note that the UNITS are in decimal degrees (latitude, longitude):

- Boulder, Colorado: 40.0274, -105.2519

- Oslo, Norway: 59.9500, 10.7500

- Mallorca, Spain: 39.6167, 2.9833

To plot these points spatially you will

- create a numpy array of the point locations and

- Use a for loop to populate a

shapelyPointobject

# Create numpy array of x,y point locations

add_points = np.array([[-105.2519, 40.0274],

[ 10.75 , 59.95 ],

[ 2.9833, 39.6167]])

# Turn points into list of x,y shapely points

city_locations = [Point(xy) for xy in add_points]

city_locations

[<shapely.geometry.point.Point at 0x7fb0b90558b0>,

<shapely.geometry.point.Point at 0x7fb0b9055910>,

<shapely.geometry.point.Point at 0x7fb0b9055970>]

# Create geodataframe using the points

city_locations = gpd.GeoDataFrame(city_locations,

columns=['geometry'],

crs=worldBound.crs)

city_locations.head(3)

| geometry | |

|---|---|

| 0 | POINT (-105.25190 40.02740) |

| 1 | POINT (10.75000 59.95000) |

| 2 | POINT (2.98330 39.61670) |

Finally you can plot the points on top of your world map. Does it look right?

# Plot point locations

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(12, 8))

worldBound.plot(figsize=(10, 5), color='k',

ax=ax)

# Add city locations

city_locations.plot(ax=ax,

color='springgreen',

marker='*',

markersize=45)

# Setup x y axes with labels and add graticules

ax.set(xlabel="Longitude (Degrees)", ylabel="Latitude (Degrees)",

title="Global Map - Geographic Coordinate System - WGS84 Datum\n Units: Degrees - Latitude / Longitude")

ax.set_axisbelow(True)

ax.yaxis.grid(color='gray', linestyle='dashed')

ax.xaxis.grid(color='gray', linestyle='dashed')

Next, import proper graticules that can be projected into a particular coordinate reference system.

# Import graticule & world bounding box shapefile data

graticule_path = os.path.join("data", "spatial-vector-lidar", "global",

"ne_110m_graticules_all", "ne_110m_graticules_15.shp")

graticule = gpd.read_file(graticule_path)

bbox_path = os.path.join("data", "spatial-vector-lidar", "global",

"ne_110m_graticules_all", "ne_110m_wgs84_bounding_box.shp")

bbox = gpd.read_file(bbox_path)

# Create map axis object

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(15, 8))

# Add bounding box and graticule layers

bbox.plot(ax=ax, alpha=.1, color='grey')

graticule.plot(ax=ax, color='lightgrey')

worldBound.plot(ax=ax, color='black')

# Add points to plot

city_locations.plot(ax=ax,

markersize=60,

color='springgreen',

marker='*')

# Add title and axes labels

ax.set(title="World Map - Geographic Coordinate Reference System (long/lat degrees)",

xlabel="X Coordinates (meters)",

ylabel="Y Coordinates (meters)");

Geographic CRS - The Good & The Less Good

Geographic coordinate systems in decimal degrees are helpful when you need to

locate places on the Earth. However, latitude and longitude

locations are not located using uniform measurement units. Thus, geographic

CRSs are not ideal for measuring distance. This is why other projected CRS

have been developed.

Projected CRS - Robinson

You can view the same data above, in another CRS - Robinson. Robinson is a

projected CRS. Notice that the country boundaries on the map - have a

different shape compared to the map that you created above in the CRS:

Geographic lat/long WGS84.

Below you first reproject your data into the robinson projects (+proj=robin). Then you plot the data once again.

# Reproject the data

worldBound_robin = worldBound.to_crs('+proj=robin')

graticule_robin = graticule.to_crs('+proj=robin')

# Plot the data

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(12, 8))

worldBound_robin.plot(ax=ax,

color='k')

graticule_robin.plot(ax=ax, color='lightgrey')

ax.set(title="World Map: Robinson Coordinate Reference System",

xlabel="X Coordinates (meters)",

ylabel="Y Coordinates (meters)")

for axis in [ax.xaxis, ax.yaxis]:

formatter = ScalarFormatter()

formatter.set_scientific(False)

axis.set_major_formatter(formatter)

What happens if you add the same Lat / Long coordinate locations that

you used above, to your map? Remember that the data on your map are in

the CRS - Robinson.

# Plot the data

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(12, 8))

worldBound_robin.plot(ax=ax,

color='k')

graticule_robin.plot(ax=ax,

color='lightgrey')

city_locations.plot(ax=ax,

marker='*',

color='springgreen',

markersize=100)

ax.set(title="World Map: Robinson Coordinate Reference System",

xlabel="X Coordinates (meters)",

ylabel="Y Coordinates (meters)")

for axis in [ax.xaxis, ax.yaxis]:

formatter = ScalarFormatter()

formatter.set_scientific(False)

axis.set_major_formatter(formatter)

plt.axis('equal');

Notice above that when you try to add lat/long coordinates in degrees, to a map

in a different CRS, the points are not in the correct location. You need

to first convert the points to the same CRS that your other data are in.

The process of converting a dataset from one CRS to another is often referred

to as reprojection.

In python, you use the .to_crs method to reproject your data.

# Reproject point locations to the Robinson projection

city_locations_robin = city_locations.to_crs(worldBound_robin.crs)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(12, 8))

worldBound_robin.plot(ax=ax,

cmap='Greys')

ax.set(title="World map (robinson)",

xlabel="X Coordinates (meters)",

ylabel="Y Coordinates (meters)")

city_locations_robin.plot(ax=ax, markersize=100, color='springgreen')

for axis in [ax.xaxis, ax.yaxis]:

formatter = ScalarFormatter()

formatter.set_scientific(False)

axis.set_major_formatter(formatter)

plt.axis('equal');

Compare Maps

Both of the plots above look visually different and also use a different coordinate system. Look at both, side by side, with the actual graticules or latitude and longitude lines rendered on the map.

# Reproject graticules and bounding box to robinson

graticule_robinson = graticule.to_crs('+proj=robin')

bbox_robinson = bbox.to_crs('+proj=robin')

# Setup plot with 2 "rows" one for each map and one column

fig, (ax0, ax1) = plt.subplots(2, 1, figsize=(13, 12))

# First plot

bbox.plot(ax=ax0,

alpha=.1,

color='grey')

graticule.plot(ax=ax0,

color='lightgrey')

worldBound.plot(ax=ax0,

color='k')

city_locations.plot(ax=ax0,

markersize=100,

color='springgreen')

ax0.set(title="World Map - Geographic (long/lat degrees)")

# Second plot

bbox_robinson.plot(ax=ax1,

alpha=.1,

color='grey')

graticule_robinson.plot(ax=ax1,

color='lightgrey')

worldBound_robin.plot(ax=ax1,

color='k')

city_locations_robin.plot(ax=ax1,

markersize=100,

color='springgreen')

ax1.set(title="World Map Projected - Robinson (Meters)")

for axis in [ax1.xaxis, ax1.yaxis]:

formatter = ScalarFormatter()

formatter.set_scientific(False)

axis.set_major_formatter(formatter)

Why Multiple CRS?

You may be wondering, why bother with different CRSs if it makes your

analysis more complicated? Well, each CRS is optimized to best represent the:

- shape and/or

- scale / distance and/or

- area

of features in the data. And no one CRS is great at optimizing all three elements: shape, distance AND

area. Some CRSs are optimized for shape, some are optimized for distance and

some are optimized for area. Some

CRSs are also optimized for particular regions -

for instance the United States, or Europe. Discussing CRS as it optimizes shape,

distance and area is beyond the scope of this tutorial, but it’s important to

understand that the CRS that you chose for your data, will impact working with

the data.

We will discuss some of the differences between the projected UTM CRS and geographic WGS84 in the next lesson.

Challenge

-

Compare the maps of the globe above. What do you notice about the shape of the various countries. Are there any signs of distortion in certain areas on either map? Which one is better?

-

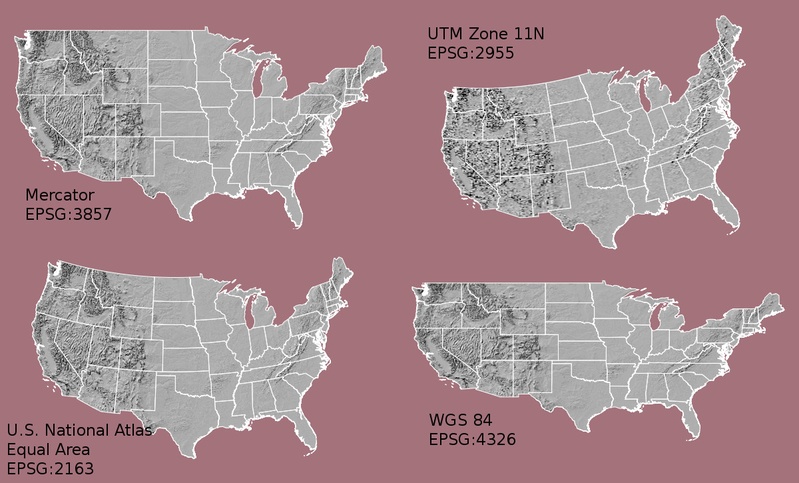

Look at the image below which depicts maps of the United States in 4 different

CRSs. What visual differences do you notice in each map? Look up each projection online, what elements (shape,area or distance) does each projection used in the graphic below optimize?

Geographic vs. Projected CRS

The above maps provide examples of the two main types of coordinate systems:

- Geographic coordinate systems: coordinate systems that span the entire globe (e.g. latitude / longitude).

- Projected coordinate Systems: coordinate systems that are localized to minimize visual distortion in a particular region (e.g. Robinson, UTM, State Plane)

You will discuss these two coordinate reference systems types in more detail in the next lesson.

Additional Resources

- Read more on coordinate systems in the QGIS documentation.

- For more on the types of projections, visit ESRI’s ArcGIS reference on projection types..

- Read more about choosing a projection/datum.

Share on

Twitter Facebook Google+ LinkedIn

Leave a Comment